Regulations

The regulation of PFAS chemistry has focused almost exclusively on two synthetic chemicals of concern: Perfluoro-octanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluoro-octane-sulphonate (PFOS).

Awareness of the widespread contamination of the environment with these compounds has grown over the last decades, alongside a growing understanding of their toxicity. This has led to restrictions in manufacture and in the market for these and associated chemicals – both through voluntary phase-out and through national and international regulations.

Many NGOs and researchers remain concerned that these restrictions do not go far enough. The phase-out in the USA and Europe has led to an increase of PFOA used in production in Asia, and often these products are still imported to Europe. The restriction of specific chemicals such as PFOA and PFOS has led to replacement for compounds with a similar chemical composition and structure. These chemical compounds have been less well studied but may have similar characteristics and environmental effects. This potential ‘regrettable substitution’ is not only potentially damaging to our environment and health, but also costly to industry, as they replace one chemical with another that may be banned in the near future. This is why NGOs often call for PFAS to be restricted as a chemical group, rather than focusing on specific chemicals.

Here we describe the current and planned regulations for PFAS chemicals around the globe, as well as voluntary phase-out initiatives.

The long-awaited PFAS RMOA was published in early April 2023. This joint Environment Agency and Health & Safety Executive report can be found here.

It makes a number of recommendations on how to manage the risks associated with PFAS, including to limit the use of PFAS-containing foams used by firefighters to put out fires, as well as the use of PFAS in textiles, furniture, and cleaning products.

The Stockholm Convention is a global treaty that aims to protect the environment and human health from the effects of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). It has been in force since 2004 and is undersigned by 152 countries of the world (although not all have ratified the agreement). POPs are chemicals that have been proven to be resistant to breakdown in the environment, able to accumulate in animals and work their way up the food chain, and are toxic or potentially toxic to animals and humans. 30 chemicals are currently restricted under the convention – those chemicals listed under Annex A are designated to be completely prohibited, for manufacture, import and export. Those under Annex B are not completely banned, but their production and manufacture is restricted. Annex C concerns substances that are unintentionally produced. Where these chemicals are produced, there must be continual efforts to reduce and, as much as possible, eliminate their emission.

PFOS has been classified as a persistent organic pollutant since 2009 and is included under Annex B of the Stockholm Convention. Restrictions apply to PFOS, its salts, as well as related chemical perfluoroctane sulfonyl fluoride (PFOSF). The use of these chemicals is currently exempted for certain uses where alternative chemicals need to be phased in, for example in electronic parts, medical devices and for use during oil production. An exemption was made for PFOS production and use on a variety of products in certain countries, which include textiles and fire-fighting foams. This exemption expired 5 years after its implementation according to Stockholm convention rules (i.e. in 2014).

PFOA was added to Annex A of the Stockholm Convention in 2019, meaning its manufacture, import and export is now prohibited. There are a few exceptions, such as production for fire-fighting foams, invasive and implantable medical devices and use in manufacture of high-voltage electrical wire, which may be permitted but only with prior registration.

PFHxS (perfluorohexane sulfanoate, a short chain alternative to PFOS), its salts and PFHxS-related compounds were also added to Annex A of the Stockholm Convention in June 2022.

How it works: REACH is a European Union Regulation that was introduced in 2006 to regulate the production and use of chemical substances. The regulations, which are thought to be the most complex introduced in the last 20 years, aim to increase traceability of chemicals in Europe, and make users and producers of chemicals more responsible for ensuring safety of their products.

The regulation classifies industrially-made chemicals into categories according to their potential effect on the environment and human health, and requires any manufacturers using a variety of chemical substances to register their use, allowing for tracking of chemical usage across Europe. Around 25,000 chemical substances have been registered under REACH by companies producing and using them. Over 200 chemicals have been classed as Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC). Companies must be authorised to use these under strict regulation and in the long term these substances will need to be substituted for less harmful ones.

PFOS was originally included in the restricted substances list of REACH. However, since its addition to the Stockholm Convention in 2009, it has been regulated under different legislation relating to its classification as a persistent organic pollutant (POP) [Regulation EC 850/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Persistent Organic Pollutants].

PFOA has been classified as a SVHC since 2013 (EU REACH Reg EC No 206-397-9). New measures to enforce tighter regulation of PFOA, its salts and related substances in the EU were introduced in July 2020 (Annex XVII, 68), in line with PFOA’s addition to Annex A of the Stockholm Convention. The restrictions include a new concentration limit of 0.025mg/kg when present in substances, mixtures or articles.

PFHxS (perfluorohexane sulfonic acid) is a short chain alternative to PFOS. In June 2017 it was also listed as a SVHC due to its environmental persistence and ability to bioaccumulate.

A phased restriction on a subset of around 200 PFAS substances, perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) containing 9-14 carbon atoms, their salts and related substances, was also announced in August, 2021. Restrictions will begin to take affect as of February 2023 under Annex XVII of REACH.

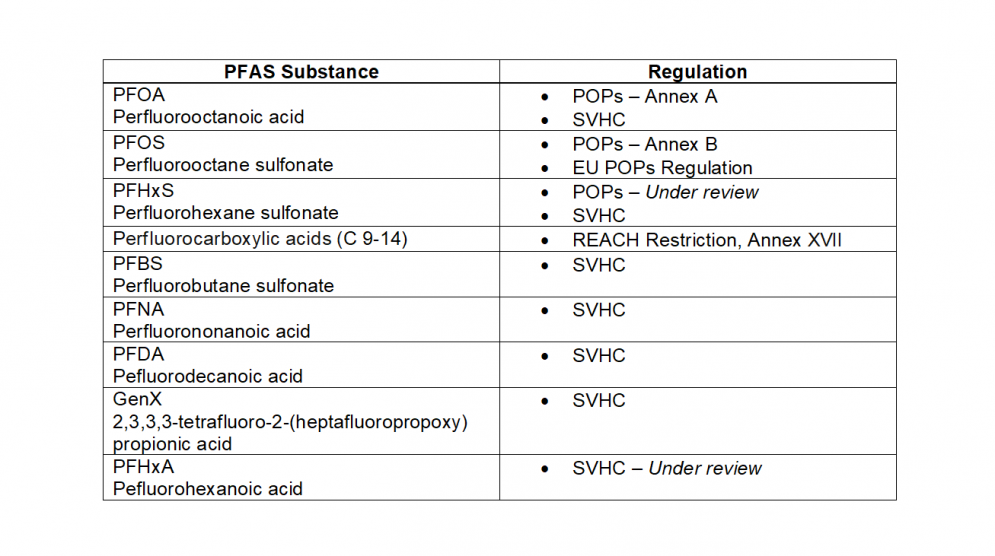

A summary of the these and other PFAS restrictions under REACH are given in the table below:

There is a lot set to change in the coming months, with the implications of BREXIT continuing to be revealed and the pending arrival of the UK Chemicals Strategy. With still so many unknowns, there is concern over the UK’s capacity to develop such a comprehensive regulatory system through UK REACH and what this could mean for the standard of chemical regulations moving forward.

For key updates on UK REACH and the UK Chemical Strategy, follow ChemTrust’s dedicated Brexit blog.

A call for change: phasing out of all non-essential PFAS

The new European Chemicals Strategy has announced the EU’s ambitious plans to ban all non-essential uses of PFAS. The strategy, released in October 2020, identifies PFAS as chemicals needing immediate attention and highlights their widespread contamination of European soil and water, as well as the ‘full spectrum of illnesses’ that PFAS have been linked to.

Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden have also agreed to prepare a joint REACH restriction proposal on PFAS. The proposal is estimated to take two years to pull together, with the potential introduction of new restrictions by 2025.

PFOS is restricted under EU laws on persistent organic pollutants, but not entirely banned. The amount of PFOS present in substances, including on textiles such as school uniforms, is restricted as follows:

| Product | Limit |

|---|---|

| Substances or preparations | The concentration of PFOS <=10 mg/kg |

| Semi-finished products or articles, or parts | The concentration of PFOS <0.1 % by weight calculated with reference to the mass of structurally or micro-structurally distinct parts that contain PFOS. |

| Textiles or other coated materials | The amount of PFOS i<1 μg/m2 of the coated material. |

| Excepted uses: | Photoresists or anti reflective coatings for photolithography processes, photographic coatings, provided certain conditions are met. |

Due to ongoing concern for product safety, some countries have decided to go beyond international and EU regulation limits for these PFASs of concern.

Denmark

As of July 2020, Denmark has become the first country to bring in legislation banning PFAS from their food packaging. Mogens Jensen, Denmark’s Minister of Food expressed that he would “not accept the risk of harmful fluorinated substances migrating from the packaging to our food. These substances represent such a health problem that we can no longer wait for the EU”.

The ban refers to all organic fluorinated compounds in paper and cardboard food packaging, and whist it is still possible for recycled paper to be used as a food contact material, materials with any level of fluorine content, now require a barrier to prevent the chemicals migrating into the food.

Norway

In 2014, Norway banned the use of PFOA in consumer products, including all solid and liquid consumer products as well as to textiles and carpets. However, the restriction does not apply to food packaging, food contact materials or medical devices. The limits related to the ban are as follows:

- PFOA in a liquid mixture – 0.001% (10 mg/kg)

- PFOA in a solid product – 0.1% (1,000 mg/kg)

- PFOA in textiles – 1 μg/m2

(i.e. same as those of PFOS across Europe).

Both PFOA and PFOS are no longer manufactured in the USA, due to voluntary phase-out by industrial leaders.

The PFOA Stewardship Program was set up in 2006 by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) inviting the 8 leading fluorinated chemistry companies to participate. The aim was to phase out emissions of PFOA, and precursors (chemicals that may transform into PFOA into the environment) from factories, with a 95% reduction proposed by 2010, and total global elimination from their processes by 2015. All participating companies met the goals of the programme, some by using alternative chemicals (e.g. short chain PFASs) in their production, others by leaving the fluorinated chemistry market entirely. This stopped the use and production of PFOA in the United States, although it is still possible to import items that contain PFOA or where it has been used in production. To ensure any new companies wishing to handle PFOA in the USA are regulated, regulations known as Significant New Use Rules (SNURs) mean new companies have to notify the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) 90 days before any import, manufacture or processing of PFOA, so that the EPA may review, and potentially place limits on any such use.

Production of PFOS in the USA was primarily through the 3M company for use in their Scotchgard product. After negotiations with the EPA in 2000, the company committed to phasing out PFOS and related chemicals (as well as PFOA) from their production.

By signing up to particular standards, companies are able to label themselves with a variety of recognisable standards. These are aimed at consumers, allowing them a level of confidence in the products they purchase above and beyond current regulations. Common textile standards include Blue Sign and Oeko-tex. Current criteria mean that both Blue Sign and Oeko-tex labelled clothing can still contain PFAS, although only short-chain varieties of non-polymers are acceptable.