Help find the PFAS

We know that PFAS are used in UK food packaging. We also know that they spread from food packaging into our environment where they can cause harm. But what we don’t know, is how widespread their use is… that’s where you come in!

You can help ‘Find the PFAS’ using this simple test. Anyone can do it, at home, with nothing more than some food packaging, a pencil and some olive oil. So why not give it a go today!

For more information, you can check out the results* to see where, and in what, other people have found PFAS.

*Please note, we are no longer taking submissions of bead test results but encourage you to contact the retailer or brand in question directly.

Please note, whilst early research indicates the effectiveness of this test to identify ‘likely’ occurrence of PFAS, it is by no means a definitive result and should not be considered as such. Further details on test accuracy are available here.

How to take part

Using paper or cardboard food packaging collected from your weekly shop or set aside from a takeaway or coffee shop treat, you can help us understand the extent of the UK’s PFAS problem.

All you need is your food packaging, some olive oil and a home-made dropper (we used a pencil!). Following the instructions in our handy video, drop a small amount of olive oil onto the packaging and tell us what you see. Does the droplet soak in, spread out, or form a perfect little bead? Top tip: trying testing both sides of the packaging.

If you have your camera or phone to hand, why not take a picture of what you’ve found.

If your result is a “bead”, we encourage you to contact the retailer or brand in question directly to let them know about the possible presence of PFAS in their products. You can use the email template here:

What type of packaging should I test?

PFAS are used to prevent oil and grease soaking into paper and cardboard packaging, so focus on these if you can. Some compostable materials, such as the compostable takeaway boxes shown in the middle photo below, also fall into this category and so are worth giving a go as well.

More examples of where PFAS are likely to be found are shown in the photos below.

Want to know about PFAS-free food packaging? You’re in luck! Visit our PFAS free products page to find out more.

Cardboard pizza box

Compostable takeaway food box

Paper food bags

What we’ve found

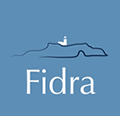

Of the items tested,

how many found a bead result?

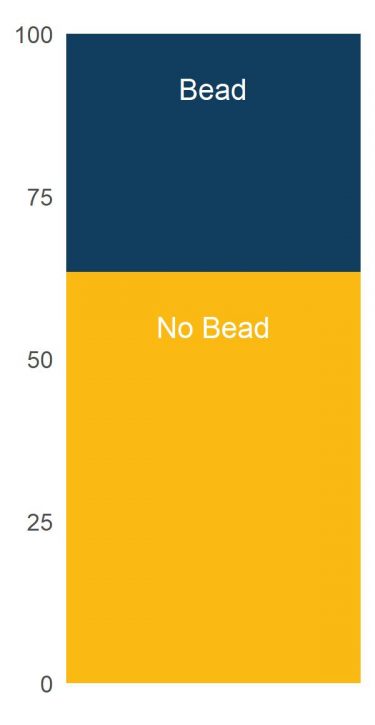

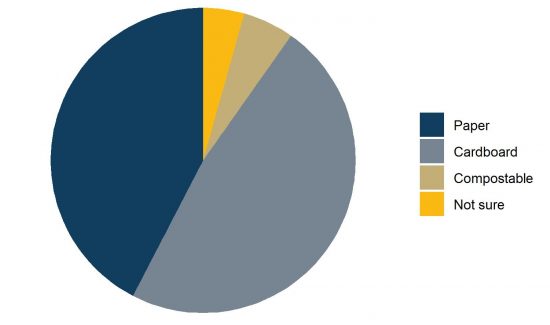

Where were the beads found?

In supermarket products…

In takeaway products…

Data accurate as of November 2022.

How we have used the results

- Targeted engagement with industry and policymakers. By showing PFAS use is widespread and identifying key sources in the UK, we used this information to refine our asks of policy makers and industry.

- Data sharing. We openly shared the data our supporters collect with interested stakeholders, be that monitoring bodies or supermarkets themselves, helping them to trace PFAS use in their own supply chains.

- Preliminary evidence for further scientific research. Our data was used by the wider research community to identify targeted samples for further, more detailed analysis.