PFAS in food packaging

‘Forever’ chemicals in ‘single use’ food packaging

PFAS, also known as ‘forever chemicals’, are prevalent in food packaging materials across the UK, despite their well-documented risks to human and environmental health [1]. These chemicals are primarily used in cardboard or paper packaging, preventing grease and moisture from weakening the material. Fast food wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, greaseproof cake liners, butter wrappers and paper for dry foods are key examples of where you might find PFAS in supermarkets, takeaways or your home [1], [2].

PFAS are not an essential ingredient in food packaging and numerous PFAS-free alternatives are readily available [3]. In fact, some retailers and even entire countries have already proposed to phase out all PFAS from food packaging materials [4], [5], [6]. Robust regulation is now urgently needed to establish a level playing field amongst businesses and retailers, and to ensure the UK maintains high standards of public and environmental protection.

This is a previous project from Fidra and not one we are actively working on at present.

Environmental risks of PFAS in food packaging

We may only use food packaging for a short time, sometimes just a few minutes, but the PFAS within them can linger in the environment for centuries. When food packaging is discarded and begins to break down, these harmful substances don’t stay put. PFAS can leak into the environment from landfills where they can contaminate soil and water sources, accumulating in wildlife and people to potentially harmful concentration levels. For items labelled as ‘recyclable’ or ‘compostable’, PFAS also risks contaminating wider materials in the circular economy, or being spread directly on to crops via compost. There is currently no effective and financially viable way to clean up PFAS already in the environment, meaning each new piece of single-use food packaging is adding to a growing problem.

Health risks of PFAS in food packaging

Food packaging is a major source of PFAS intake for humans [7], [8] — people eating more food packaged in materials containing PFAS have been found to have higher levels of these chemicals in their blood [9]. PFAS migration into food is thought to be particularly prevalent for fatty foods, when a greaseproof PFAS layer is more likely to be used [10]. Some well-researched PFAS have been linked with numerous significant health concerns including cancers [11], [12], [13], [14], liver damage [15] and various reproductive health issues [16], [17], highlighting the importance of a group-based PFAS restriction to prevent this unnecessary risk to public health.

Our work on PFAS in food packaging

In 2020 Fidra conducted research into the presence of PFAS in UK supermarket and takeaway own-brand food packaging. Results found PFAS in packaging from 8 out of 9 major UK supermarkets and in 100% of takeaways tested. In 2021, we delivered a petition containing almost 12,000 signatures to the CEO’s of Aldi, ASDA, Co-op, Iceland, Lidl, Morrisons, Marks and Spencer, Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Waitrose, urging them to remove PFAS from UK food packaging. Three supermarkets subsequently committed to phasing PFAS out of their own-brand food packaging and others committed to investigating the issue further.

Whilst this reflects some progress, the UK remains slow to act in contrast to other countries. For example, Denmark committed to a ban on PFAS in paper and cardboard and food packaging in 2020 [5] and the proposed universal PFAS restriction across the EU will likely cover all food packaging, should it come into force [18]. Fidra are continuing to call on the UK Government for a group-based restriction on PFAS in food packaging, as part of a wider ambitions to achieve a PFAS-free economy in the UK.

The Bead Test – find the PFAS!

The best test is a simple test that can indicate whether PFAS may be present in food packaging materials, using only a pencil and some olive oil. The chemical properties of PFAS mean that they typically function as an ‘oil repellent’ meaning that oil droplet should form distinct ‘beads’ on the surface of packaging.

Where were the PFAS found?

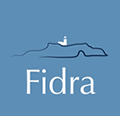

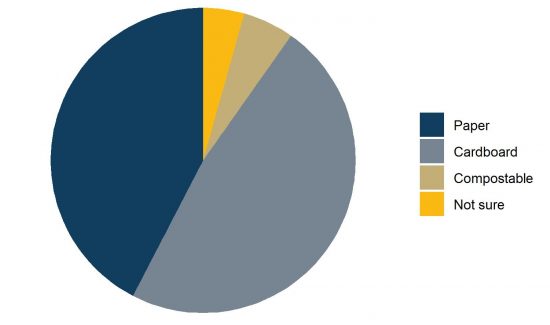

Fidra screened almost 100 different types of food packaging using the bead test, from a broad range of UK retailers. We found that around 30% of the packaging was likely to contain PFAS and that the ‘bead test’ methodology was highly accurate when compared to the results from laboratory testing for PFAS.

In supermarket products…

In takeaway products…

Data accurate as of November 2022.

Progress from UK retailers

The following data is accurate as of September 2022. Fidra are no longer actively pursuing updates from UK supermarkets.

*The information presented here is based on that provided by companies own communication or other referenced data sources and only accounts for intentionally added PFAS rather than potential background contamination. Fidra has not carried out independent verification, unless otherwise stated.

Resources

Vegware Case Study

The popularity of compostable food packaging is increasing as producers look to reduce their reliance on single use plastics. However research has shown that many compostable food packaging options contain PFAS. This can result in contamination of compost and subsequently crops with PFAS from the compostable food packaging.

VegWare aim to address this with the introduction of the VegWare Nourish range of compostable, no added PFAS food packaging.

Published: Dec 2023

Author: Fidra

Throwaway Packaging, Forever Chemicals – European-wide survey of PFAS in disposable food packaging and tableware

This report is based on a European study looking at the presence of PFAS in disposable paper, board and moulded fibre food packaging items. It aims to understand the widespread use of intentionally added PFAS in food packaging, as well as looking at background contamination levels.

Published: May 2021

Authors: Collaborative works of Arnika Association (Czech Republic), CHEM Trust, BUND/Friend of the Earth (Germany), Danish Consumer Council (Denmark), The Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) (Belgium), Tegengif – Erase all Toxins (The Netherlands), Générations Futures (France) and IPEN

Forever Chemicals in The Food Aisle

This report provides information on the presence of PFAS in disposable paper, board and moulded fibre food packaging across a number of major UK supermarkets and food-to-go outlets. The report also describes the ‘bead test’, now widely used as a preliminary indication of intentionally added PFAS prior to further testing.

Published: Feb 2020

Author: Fidra

PFAS and Alternatives in Food Packaging: Report on the commercial availability and current uses

This report outlines availability of current alternatives, both chemical and non-chemical, to PFAS in paper and paperboard food packaging. The work was completed within the framework of the OECD/UNEP Global Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFC) Group.

Published: 2020

Author: OECD

Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food

This report details the risk of exposure and likely health outcomes from four major PFAS found in food products. Although it is focussed on the EU, the contents of the report can be applied more widely.

Published: Sep 2020

Author: European Food Safety Authority

How UK Retailers are Tackling Chemicals of Concern: A case for group-based chemical legislation

This report summarises retailer progress towards sustainable chemical management utilising examples from two chemical groups of concern, PFAS and bisphenols. Fidra has worked with some of the UK’s leading supermarkets, food outlets and high-street retailers, and have seen an increase in support for a group-based approach to chemical legislation from these key stakeholders.

Published: November 2021

Author: Fidra

References

[1] Fidra, “Forever chemicals in the food aisle: PFAS content of UK supermarket and takeaway food packaging,” Feb. 2020. Accessed: Jan. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.pfasfree.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Forever-Chemicals-in-the-Food-Aisle-Fidra-2020-.pdf

[2] L. Minet et al., “Use and release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in consumer food packaging in U.S. and Canada,” Environ Sci Process Impacts, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 2032–2042, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1039/D2EM00166G.

[3] A. Yashwanth et al., “Food packaging solutions in the post-per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and microplastics era: A review of functions, materials, and bio-based alternatives,” Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf, vol. 24, no. 1, p. e70079, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.70079.

[4] ChemTrust, “EU bans sub-group of PFAS used in food packaging and clothing.” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://chemtrust.org/eu_pfhxa_ban/

[5] Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark, “Ban on fluorinated substances in paper and board food contact materials (FCM).” Accessed: Nov. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: moz-extension://0945a07c-05cc-47a7-9b65-bb8b3160183f/enhanced-reader.html?openApp&pdf=https%3A%2F%2Fen.foedevarestyrelsen.dk%2FMedia%2F638210239823191854%2FFaktaark%2520FCM%2520(english).pdf

[6] CHEMTrust, “McDonald’s announces global PFAS ban in food packaging.” Accessed: Nov. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://chemtrust.org/news/mcdonalds-pfas-ban/

[7] E. M. Sunderland, X. C. Hu, C. Dassuncao, A. K. Tokranov, C. C. Wagner, and J. G. Allen, “A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects,” Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology 2018 29:2, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 131–147, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41370-018-0094-1.

[8] X. C. Hu et al., “Can profiles of poly- and Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in human serum provide information on major exposure sources?,” Environ Health, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Feb. 2018, doi: 10.1186/S12940-018-0355-4/FIGURES/6.

[9] H. P. Susmann, L. A. Schaider, K. M. Rodgers, and R. A. Rudel, “Dietary habits related to food packaging and population exposure to PFASs,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 127, no. 10, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1289/EHP4092/SUPPL_FILE/EHP4092.S002.CODEANDDATA.ACCO.ZIP.

[10] H. Choi, I. A. Bae, J. C. Choi, S. J. Park, and M. K. Kim, “Perfluorinated compounds in food simulants after migration from fluorocarbon resin-coated frying pans, baking utensils, and non-stick baking papers on the Korean market,” Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 264–272, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1080/19393210.2018.1499677.

[11] V. Barry, A. Winquist, and K. Steenland, “Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Exposures and Incident Cancers among Adults Living Near a Chemical Plant,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 121, no. 11–12, pp. 1313–1318, Nov. 2013, doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306615.

[12] V. Barry, A. Winquist, and K. Steenland, “Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) exposures and incident cancers among adults living near a chemical plant,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 121, no. 11–12, pp. 1313–1318, Nov. 2013, doi: 10.1289/EHP.1306615/SUPPL_FILE/EHP.1306615.S001.508.PDF.

[13] M. van Gerwen et al., “Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure and thyroid cancer risk,” EBioMedicine, vol. 97, Nov. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104831.

[14] V. M. Vieira, K. Hoffman, H.-M. Shin, J. M. Weinberg, T. F. Webster, and T. Fletcher, “Perfluorooctanoic Acid Exposure and Cancer Outcomes in a Contaminated Community: A Geographic Analysis,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 121, no. 3, pp. 318–323, Mar. 2013, doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205829.

[15] E. Costello et al., “Exposure to per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Markers of Liver Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 130, no. 4, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1289/EHP10092/SUPPL_FILE/EHP10092.S002.CODEANDDATA.ACCO.ZIP.

[16] B. P. Rickard, I. Rizvi, and S. E. Fenton, “Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and female reproductive outcomes: PFAS elimination, endocrine-mediated effects, and disease,” Toxicology, vol. 465, p. 153031, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1016/J.TOX.2021.153031.

[17] K. K. Hærvig et al., “Maternal Exposure to Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Male Reproductive Function in Young Adulthood: Combined Exposure to Seven PFAS,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 130, no. 10, pp. 1–11, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1289/EHP10285/SUPPL_FILE/EHP10285.S001.ACCO.PDF.

[18] ECHA (The European Chemicals Agency), “Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).” Accessed: Jan. 16, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/perfluoroalkyl-chemicals-pfas.