From everyday products, PFAS have made their way into our food, our homes and our bodies. Even now, with growing evidence of their harmful impacts, they continue to be used and pollute natural environments all over the world. Here we look to the policies supposedly set out to protect both our health and the environment and ask why PFAS remain a threat today.

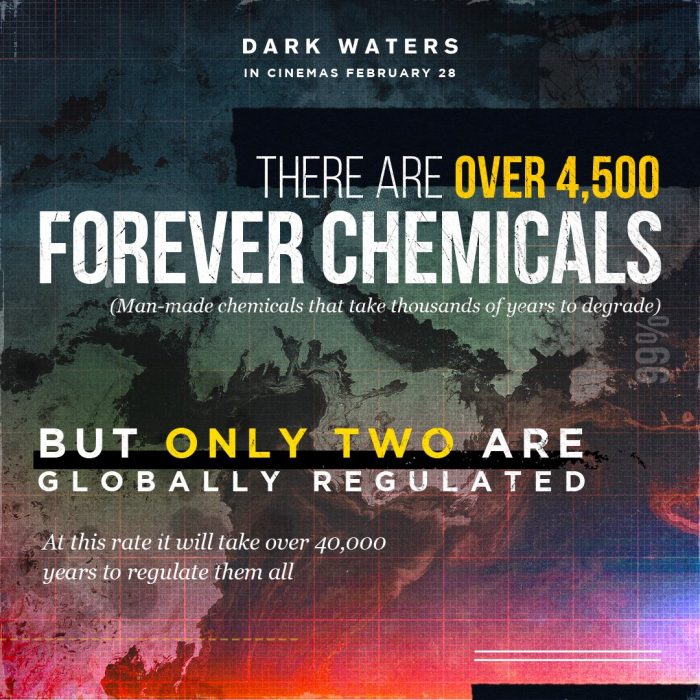

PFAS are a group of over 4,700 industrial chemicals used in everyday items: from clothing and cosmetics, to furniture and food packaging. Some of these ‘forever chemicals’ can remain in the environment for over 1,000 years, building up in soils, rivers and oceans, and on into plants, animals and people across the globe.

So, why is this an issue? PFAS can be toxic to both people and wildlife. Studies have shown PFAS damage the immune system of bottlenose dolphins and otters. There is also growing evidence that links PFAS exposure to a wide range of human health concerns, including cancer, immune system disorders, fertility issues and obesity.

Awareness of the PFAS problem has never been greater and, rightly so, the question of ‘what is being done to protect us and the environment?’, continues to be asked. So, what are the UK PFAS protections, and where could we be heading in the not too distant future?

Why aren’t all PFAS banned?

Despite the huge, and growing, number of PFAS available for use, only a handful are subject to restrictions, anywhere in the world. In fact, it is often much harder for governments to regulate a chemical than it is for industry to use a chemical. The body of evidence that proves harm needs to be sufficient to outweigh the economic benefits of continued use, and this, it seems, is a very difficult criteria to meet. Here’s an outline of where we are so far.

The Stockholm Convention

The most wide-reaching current regulation is the Stockholm Convention, a global treaty signed by 152 countries, including the UK, which aims to protect both human health and the environment from Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). POPs are chemicals which have been shown to be persistent in the environment, with a global reach and harmful impacts on human health or the environment. Being listed in the Stockholm Convention is as close as a chemical can come to being globally banned or restricted.

So far only two PFAS, perfluoro-octane-sulphonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), have been officially identified as POPs, with one other, perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS), under review. PFOA, the most recent addition, was listed under Annex A of the Stockholm Convention in 2019, meaning its manufacture, import and export is now largely prohibited, with very few exceptions.

Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of Chemicals (REACH)

REACH is an EU regulation responsible for one of the most comprehensive chemical databases in the world, with approximately 25,000 chemicals currently registered from all over Europe. Managed by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), REACH was introduced to help protect both human and environmental health from harmful chemical exposure.

REACH requires companies to register their chemical substances, along with any identified risks associated with their use. These registrations are then to be evaluated by ECHA who will assess whether such risks can be adequately managed.

REACH recognises six PFAS as Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC), with one other under review. Substance of Very High Concern classification means that a chemical has been identified as harmful but may still be used in products temporarily whilst safer, longer-term alternatives are identified. Under this classification, consumers have a legal right to know whether a product contains any Substances of Very High Concern, known as ‘SVHC right to know’. However, to find out this information, a consumer must submit a formal request to the suppliers of the product and may have to wait up to 45 days for a response. In practice, this means that consumers can’t find out about PFAS in products at point of purchase.

Water Framework Directive

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is an EU regulation intended to protect European waters from harmful pollutants. Under the WFD, one specific PFAS, PFOS, is recognised as a ‘priority hazard substance’. This means that PFOS has been identified as harmful to the environment, so much so that the UK’s Environment Agency is required to continually monitor, report on and, where levels exceed Environmental Quality Standards (EQS), make efforts to reduce PFOS concentrations found in both water and wildlife.

UK chemical regulation after Brexit transition period

There is a lot set to change in the coming months, with the implications of BREXIT continuing to be revealed and the pending arrival of the UK Chemicals Strategy.

From latest government discussions, it now looks like a UK REACH is the most likely outcome for chemical regulation at the end of the Transition Period. Exactly how this will work and how long it will take remains to be seen, however we have been assured that current EU chemical restrictions will be upheld throughout this transitionary period. With so many unknowns, there is concern over the UK’s capacity to replicate such a comprehensive regulatory system and what this could mean for the standard of chemical regulations in the future.

A consultation on a draft of the UK Chemical Strategy is due to take place in 2021-22 and is expected to outline the main government priorities for the sector.

It could therefore be some time before the government clarifies what the UK’s approach to PFAS will look like, so in the meantime, we’ve had look at how other countries have tackled PFAS and what the UK might be able to learn from their examples.

Denmark: Front runners in protecting consumers from PFAS

Denmark has decided it wants to go further than current EU regulations and, as of July 2020, will be banning PFAS from use in all paper and board food packaging. The ban will allow exceptions for PFAS already present in recycled packaging. However, in these cases there must be a protective layer present between the packaging and the food.

In comparison to the EU’s current one-by-one approach to chemical legislation, Denmark’s group-based approach to PFAS regulation gives faster, more comprehensive protection from PFAS; as Denmark’s Minister of Food, Morgen’s Jensen’s, has said “these substances represent such a health problem that we can no long wait for the EU”.

The Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Luxemburg & Germany: Calling for phasing out non-essential PFAS

The Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Luxemburg and Germany have all also expressed their desire for a group-based approach and are pushing for comprehensive action on all non-essential PFAS in all products.

In a letter to the EU in December 2019, they called for a future allowing only essential use of PFAS and for a group-based approach to be taken rather than the “current inefficient substance-by-substance assessment”.

Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden have agreed to prepare a joint REACH restriction proposal on PFAS. The call for evidence for this proposal opened in May 2020, with the five countries encouraging scientists, NGOs and companies that make and use PFAS to come forward and provide information. Once the call for evidence closes in July of this year, the proposal is expected to take two years to pull together. All being well, restrictions could come into force as of 2025.

United States of America: Progressing state by state

At least 30 states have now acted above and beyond that of the US government to protect their citizens and the environment from the impacts of PFAS. Efforts range from additional funding for research and monitoring, free blood-testing for those thought to be especially vulnerable to contamination, and the development of entire taskforces specifically created to tackle the PFAS problem.

Numerous states are also either in the process of, or have already, introduced tighter restrictions on the use of PFAS, one the most common being PFAS in food packaging materials. Arizona, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Virginia are just some of the states currently fighting to remove these chemicals from their food packaging.

United Kingdom…

The ever-mounting evidence of harm that can be caused by PFAS has sparked many citizens, scientist, NGOs, regulators, and businesses, in countries all over the world to step-up and take action. There can now be no doubt of the need for a faster-acting and more holistic approach to PFAS regulation.

The UK has the chance to set higher standards, to introduce tougher measures, to invest in research and monitoring, and to provide real protection to both public health and the environment from PFAS pollution. Outside regulation, positives steps are already being taken, such as voluntary phase-outs from retailers and greater public involvement with the PFAS problem. Whether the UK government will follow suit remains to be seen, but we have had assurance from one Defra Minister that a group-based approach to PFAS is the way forward and so, with growing support from consumers, companies and retailers, perhaps effective PFAS regulation is right around the corner…

If you want to reduce your PFAS use and help influence change, you can!

- Sign and share our petition to remove PFAS from paper and board food packaging

- Try out our ‘bead-test’ to help us track down the source of PFAS from UK retailers

- Learn more on PFAS in consumer goods and checkout our PFASfree shopping guide